During the AI research boom of the 1970s, the LISP language – from LISt Processor – saw a major surge in use and development, including many dialects being developed. One of these dialects was Scheme, developed by [Guy L. Steele] and [Gerald Jay Sussman], who wrote a number of articles that were published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) AI Lab as part of the AI Memos. This subset, called the Lambda Papers, cover the ideas from both men about lambda calculus, its application with LISP and ultimately the 1980 paper on the design of a LISP-based microprocessor.

Scheme is notable here because it influenced the development of what would be standardized in 1994 as Common Lisp, which is what can be called ‘modern Lisp’. The idea of creating dedicated LISP machines was not a new one, driven by the processing requirements of AI systems. The mismatch between the S-expressions of LISP and the typical way that assembly uses the CPUs of the era led to the development of CPUs with dedicated hardware support for LISP.

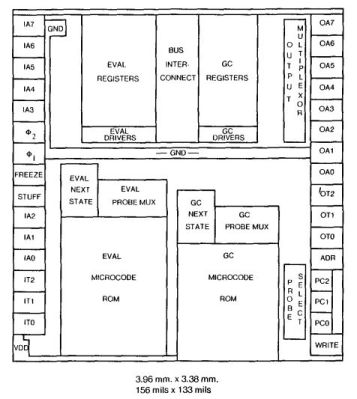

The design described by [Steele] and [Sussman] in their 1980 paper, as featured in the Communications of the ACM, features an instruction set architecture (ISA) that matches the LISP language more closely. As described, it is effectively a hardware-based LISP interpreter, implemented in a VLSI chip, called the SCHEME-78. By moving as much as possible into hardware, obviously performance is much improved. This is somewhat like how today’s AI boom is based around dedicated vector processors that excel at inference, unlike generic CPUs.

During the 1980s LISP machines began to integrate more and more hardware features, with the Symbolics and LMI systems featuring heavily. Later these systems also began to be marketed towards non-AI uses like 3D modelling and computer graphics. As however funding for AI research dried up and commodity hardware began to outpace specialized processors, so too did these systems vanish.

Top image: Symbolics 3620 and LMI Lambda Lisp machines (Credit: Jason Riedy)